Motivation

Motivation: Overview

One definition of motivation is the desire and drive to do something.

It's the difference between waking up excited to face the day's tasks and battling to get up and going.

Motivation can be as simple as hunger motivating us to eat, ambition driving us to work towards a final exam, duty to empty the dishwasher, or parental love leading us to care for a child.

According to psychology, motivation encompasses drives, desires, needs, and objectives.

From a neuroscience perspective, motivation is linked to the brain's reward system, emphasising neurotransmitters like dopamine. Dopamine is the neurotransmitter in the brain's reward circuits linked to pleasure and learning.

The Neuroscience of Motivation

Exploring the neuroscience of motivation gives insight into how your brain orchestrates the impulses that propel you into action. Understanding the neural mechanisms offers additional insight into the very essence of human behaviour and the pursuit of goals.

Homeostasis as the Biological Basis of Motivation

What propels us to act?

The answer lies partly in homeostasis, the process by which organisms maintain internal physiological stability.

For example, the sense of urgency you feel when you're thirsty shows how much our body needs us to behave in specific ways. When you respond to thirst by drinking water, you restore homeostasis, and the resulting relief is a form of reward, reinforcing the behaviour the next time you feel thirsty.

While animals primarily seek basic needs like food, water, and safety, human desires extend to complex and varied wants such as a luxury label car or purse, indulgent entertainment, and social status or recognition. This complexity raises the question of how simple animal drives (like thirst) evolved into the diverse array of human desires (like needing thousands of likes on an Instagram post).

Dopamine: Excitement and Disappointment

One hallmark of the nervous system is its ability to change in response to experiences through learning. You are constantly learning from our experiences and the consequences of our actions.

But how do you learn what to seek out and what to avoid?

The neuromodulator dopamine provides a teaching signal about whether a behaviour was worthwhile doing or not and if it should be done again.

"Reward prediction error" is the term used for the mismatch between the reward you expect and what you actually get.

Because dopamine neurons are always electrically active, think of them as humming along at a baseline rate; they can change their activity by firing faster or slower in response to different situations.

- When you receive an unexpected reward, dopamine neurons fire more than anticipated. This feels like satisfaction, pleasure or relief. It makes us want to do that action again, hence feeling more motivated to act again.

- Conversely, if an expected reward isn't received, there's a decrease in dopamine activity. This feels like disappointment. This lack of expected reward diminishes our motivation because the brain learns that the action should be avoided.

Over time, these prediction errors help the brain refine its expectations. They play a critical role in learning, enabling us to identify and seek out behaviours that lead to rewards (or not).

The Psychology of Motivation

According to social psychologist Roy Baumeister, “Motivation is wanting.”

Baumeister’s phrase is closely related to psychologist William James’s famous line “Wanting is for doing!”.

Because you’re an animal (not a plant), your ability to move about and change your environment means motivation and moving (i.e. doing) are closely related. Thus, similar neural circuitry is involved in movement and motivation, and both movement and motivation require the neurotransmitter dopamine.

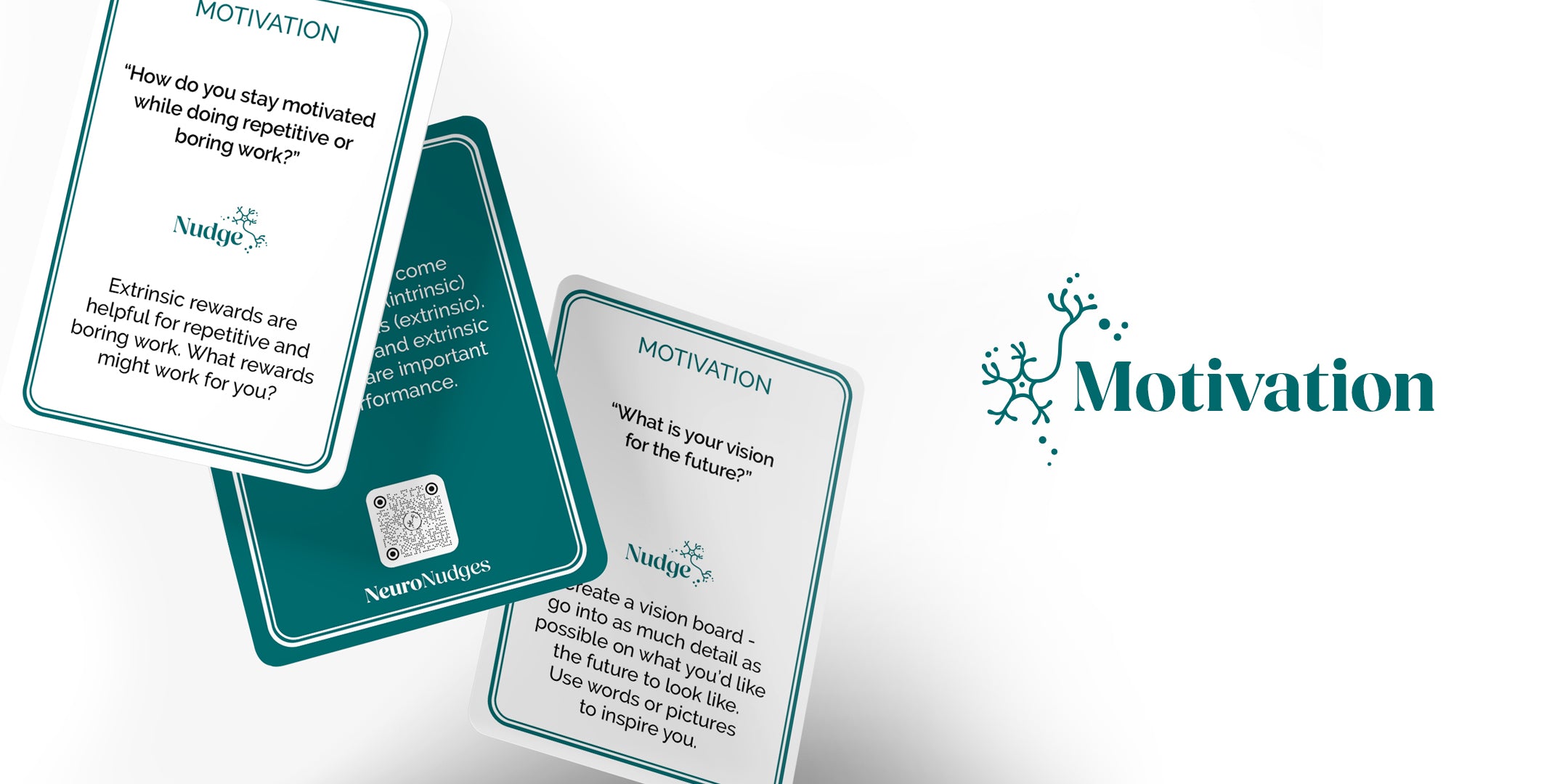

Intrinsic Versus Extrinsic Motivation: What Matters More?

How can you motivate yourself or others?

Some activities you do just because it feels good or it's interesting. Other times you act for a reward or to dodge a penalty.

Which is more powerful?

- Intrinsic motivation arises from an internal desire to act because it's personally rewarding, e.g., a dancer might dance purely for the love and joy it brings.

- Extrinsic motivation stems from external rewards or consequences, e.g. an employee might work overtime not out of passion but for a bonus. Extrinsic motivators often include prizes, money or praise.

Think of intrinsic motivation as reading a book because you're genuinely curious about the plot and extrinsic motivation as reading because there's a test tomorrow.

In essence, while intrinsic motivation is fuelled by personal interest or enjoyment, extrinsic motivation is driven by external factors or outcomes.

The relative importance of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation depends on the context and the desired outcomes. Both types of motivation have their advantages and limitations.

For example, the context often determines which form of motivation is more effective. Intrinsic motivation tends to be more beneficial for long-term engagement and deep cognitive tasks. For specific, short-term goals, extrinsic motivators can be powerful. The value and impact of each motivation type can also vary across cultures. And in some cultures, extrinsic rewards like societal recognition might be more potent than in others.

Self-determination theory: understanding intrinsic motivation

Self-determination theory states three basic psychological needs should be satisfied to enhance intrinsic motivation.

- Autonomy: people need to feel that they are the masters of their destiny and have at least some control over their lives; most importantly, they need to think that they control their behaviour.

- Competence (also called Mastery): another need concerns our achievements, knowledge, and skills; people need to build their competence and develop mastery over essential tasks.

- Relatedness (also called Connection): People need a sense of belonging and connectedness; each of us needs others to some degree.

Additional Strategies for Motivation

Practical strategies like motivational interviewing can be powerful tools in a coach's arsenal.

Motivational interviewing enables you to explore your motives and commit to change in a supportive setting through motivational interviewing.

Coaches and teachers can help their clients and students find their own inspiration and boost their drive to reach their goals by actively listening and encouraging them to think about what they are saying.

Relevance to Coaching Practice

Understanding the neurobiological basis of motivation can give coaches a practical way to understand and improve their coaching methods.

For instance, understanding how the brain learns from experiences and actions is key to understanding motivation. Knowing that dopamine acts as a teacher, signalling both surprise and disappointment, might be helpful information to share with someone struggling to get motivated after a let-down.

Coaches can guide their clients more effectively using ideas from Self-Determination Theory and methods like motivational interviewing. This helps clients achieve their goals and gives coaches a solid basis to their coaching conversations.

Motivation: Summary

Motivation is what gets you up and going, whether it's the simple of doing something we love, the push of a prize, or the desire to stay out of trouble. If we understand this, especially how dopamine works in our brains as a reward prediction error ‘teacher’, it can help us find our groove, whether we're trying to get over a disappointment or feel like we might just have another go.

The Neuro Nudges team wish you well as you have another go!

Recommended Resources

Books

- Balcetis, E. (2020). Clearer, Closer, Better: How Successful People See the World. Ballantine Books.

- Grant, A (2023). Hidden Potential: The Science of Achieving Greater Things. WH Allen.

- Lieberman, D. Z., & Long, M. E. (2019). The Molecule of More. BenBella Books.

Podcasts

- Huberman Lab. (2023). Goals Toolkit: How to Set & Achieve Your Goals. [Audio podcast].

- Huberman Lab. (2023). How to Use Music to Boost Motivation, Mood & Improve Learning. [Audio podcast].

- Huberman Lab. (2021). Dopamine, Mindset and Drive. [Audio podcast].

- Huberman Lab. (2022). How to Increase Your Motivation and Drive. [Audio podcast].

- Unlocking Us (2022). Brené with Karen Walrond on Accessing Joy and Finding Connection in the Midst of Struggle. [Audio podcast].

Other Resources

- Hall et al (2013). Motivational interviewing techniques. Facilitating behaviour change in the general practice setting. Australian Family Physician, 41(9), 660-667.

- Huberman, A. (2022). Tools to Manage Dopamine and Improve Motivation & Drive. Neural Network Newsletter.

Academic

- Baumeister, R. (2016). Toward a general theory of motivation: Problems, challenges, opportunities, and the big picture. Motivation and Emotion, 40(1), 1–10.

- Cerasoli et al. (2014). Intrinsic motivation and extrinsic incentives jointly predict performance: A 40-year meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 980–1008.

- Deci & Ryan. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology / Psychologie Canadienne, 49(3), 182–185. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012801

- Hardcastle et al. (2015). Motivating the unmotivated: how can health behaviour be changed in those unwilling to change? Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 835.

- Ryan & Deci. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61,

Links to the other neuroscience resources pages

Click here to download and print this page.

Click here for the Members' Portal

Copyright © Dr Sarah McKay 2024

Reproduction, adaptation, or use of this material beyond personal or one-to-one coaching use is strictly prohibited without written permission.